Happy Feet Two meets the criteria of the Enviro-Toon well. It shows us scenes of Ramon (Robin Williams) struggling to escape an oil spill and watch the spill flame up in a spectacular oil fire. It also explains The Mighty Sven’s (Hank Azaria) dilemma to introduce the film’s central conflict, the negative repercussions of global warming. Sven has lost his icy home to global warming. With warming temperatures, the ice melted, revealing open waters and green grasses that are uninhabitable to puffins.

This blog explores popular film and media and their relationship to the environment.

Saturday, September 24, 2022

Happy Feet Two as Enviro-Toon

Happy Feet Two meets the criteria of the Enviro-Toon well. It shows us scenes of Ramon (Robin Williams) struggling to escape an oil spill and watch the spill flame up in a spectacular oil fire. It also explains The Mighty Sven’s (Hank Azaria) dilemma to introduce the film’s central conflict, the negative repercussions of global warming. Sven has lost his icy home to global warming. With warming temperatures, the ice melted, revealing open waters and green grasses that are uninhabitable to puffins.

Saturday, September 17, 2022

Addressing Everyday Eco-Disasters in Happy Feet Two

For us, despite the film’s weaknesses, Happy Feet Two embraces a broader environmental message than that found in the original Happy Feet film. Happy Feet illustrates a clear eco-problem: overfishing. But the film offers a single unrealistic solution: human intervention to ensure sustainable fishing practices and protect penguins because they dance and sing like humans.

Saturday, September 10, 2022

Illustrating Everyday Eco-Disasters in Film

Recent documentaries and feature films explore and argue against everyday eco-disasters. With explorations of films as diverse as Dead Ahead, a 1992 HBO dramatization of the Exxon Valdez disaster, Total Recall (1990), a science fiction feature film highlighting oxygen as a commodity, The Devil Wears Prada (2006), a comment on the fashion industry, and Food, Inc. (2009), a documentary interrogation of the food industry, our projects explore documentaries and feature films as film art to determine how successfully they fulfill their goals.

Saturday, September 3, 2022

Negative Externalities and Fair Vs. Wise Use

Gasland (2010) documents multiple ways natural gas drilling causes negative externalities, threatening upper water supplies in the Delaware basin, for example. Documentaries highlight multiple types of negative environmental externalities: Genetically engineered seed has produced resistant super weeds, and carp introduced in the Chicago River are threatening other fish in Lake Michigan and the other Great Lakes. Environmental externalities have a global effect negatively impacting water, air, housing, energy production, and quality of human and nonhuman life around the world.

Saturday, August 27, 2022

Negative Exteranalities in Documentaries

The term “externality” comes from economics and refers to “an economic choice or action by one actor that affects the welfare of others who are not involved in that choice or action” (Goodwin, et al). Although externalities can be positive, as when “a landowner, by choosing not to develop her land might preserve a water recharge source for an aquifer shared by the entire local community” (Goodwin, et al), environmental externalities are most often negative.

Saturday, August 20, 2022

The Rhetoric of the Eco-Documentary

Although many would argue that all texts, including documentaries, are inherently rhetorical, since they address an audience from a particular standpoint, historically, the rhetorical documentary presents an argument and lays out evidence to support it. In The Rhetoric of the New Political Documentary, however, Thomas W. Benson and Brian J. Snee assert, “The rhetorical potential of documentary film… relies not on an audience who merely provides the rhetor with resources that might be exploited in persuasion but instead on an audience who is actively engaged in judgment and action” (137).

Audiences do not merely mimic the action on the screen, according to Benson and Snee. They interpret the actions documented, and invent and engage in acts of their own that respond to the film’s rhetoric, but from the viewer’s perspective. Some of our work examines this rhetorical potential in relation to food industry documentaries. The best of these eco-documentaries fulfill Paula Willoquet-Maricondi’s definition, “to play an active role in fostering environmental awareness, conservation, and political action…, that is, to be a member of the planetary ecosystem or ‘ecosphere and, most important, to understand the value of this community in a systemic and nonhierarchical way (10).”

When taking a rhetorical approach, documentation of actions also seems to adhere to the criteria Karl Heider outlines for ethnographic filmmaking, when explaining, “the most important attribute of ethnographic film is the degree to which it is informed by ethnographic understanding” (5). According to Heider, first of all, “ethnography is a way of making a detailed description and analysis of human behavior based on a long-term observational study on the spot,” (6). Secondly, Heider suggests that ethnography should “relate specific observed behavior to cultural norms” (6). The individual narratives these films provide also support Heider’s third criteria for an effective ethnography: “holism” (6). These interconnected stories are “truthfully represented” (Heider 7) according to Heider’s final criterion for an effective ethnographic film, all in service to the films’ rhetoric.

Saturday, August 13, 2022

Human Ecology and Self-Sufficiency Standard

For a working adult in Illinois, an hourly wage of at least $8.57/hour was necessary in 2002 to earn the $1508 per month (with 176 hours per month of work) or $18,097 per year salary necessary to meet housing, food, transportation, miscellaneous, and tax expenses (Pearce and Brooks 8). For a family of four, with two working adults, a pre-school child, and a school-age child, an hourly wage of at least $10.07 per adult was necessary in 2002 to earn the $3543 per month (for 176 hours per month of work) or $42,519 per year required to meet these same basic needs, as well as child care expenses (Pearce and Brooks 8).

Saturday, August 6, 2022

Human Ecology and Basic Needs

Much of our research explores films associated with our basic needs (air, water, food, clothing, shelter, and energy), and the everyday eco-disasters associated with their exploitation. Such exploitation is typically associated with a “fair use” model of ecology, which grew out of economic approaches to the environment connected to Social Darwinism.

Friday, July 29, 2022

Dead Ahead: Exxon Valdez Oil Disaster in Context, conclusion

More importantly, in Dead Ahead Iarossi revealed that Exxon knew about Hazelwood’s drinking problem but allowed him to continue as captain of the Valdez. Iarossi resigned from Exxon in 1990 and became president of the American Bureau of Shipping, “a nonprofit corporation that classifies ships for insurers, inspects blueprints during construction and surveys vessels to make sure they are seaworthy” (“Where are They Now?). According to a 1999 Anchorage Daily New article, Iarossi told The Business Times of Singapore, “What we need to do is to try to develop much more of a safety culture, the mentality which is very much safety-oriented on the part of shipping companies and ship operating officers.” The film draws on this same representation of Iarossi as a figure disillusioned by Exxon’s failure to address safety issues to reinforce its argument for double hulled tankers, but not against oil.

Friday, July 22, 2022

Dead Ahead: Exxon Valdez Oil Disaster in Context, continued

From its opening scenes showing Captain Joseph Hazelwood’s (Jackson Davies) absence from the bridge because of alcohol abuse to its dramatization of conflicts between the U.S. EPA and its local representative, Dan Lawn (John Heard) and between Exxon and its spokesperson, Frank Iarossi (Christopher Lloyd), Dead Ahead effectively addresses the post-spill disaster, arguing both through its narrative and cinematic portrayals of once-pristine waters and landscapes for double hulls in oil tankers and better implementation of protocols if and when another spill occurs. It does not, however, argue against the production and transporting of oil because, as Woodhead states, “America cannot afford to be without (oil) supply, but we better try to do a lot better in controlling how we get it out of there” (King).

Friday, July 15, 2022

Dead Ahead: The Exxon Valdez Oil Disaster in Context

Dead Ahead: The Exxon Valdez Disaster focuses primarily on the reasons behind both the spill and its slow cleanup, however, rather than on the inherently dangerous consequences of oil production and shipment. To reinforce this assertion that safety regulations, not the oil industry per se, caused this horrendous disaster and its catastrophic consequences, the film provides a reenactment of the 1989 Exxon Valdez tanker catastrophe, from the moments before the tanker ran aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound, rupturing its storage tanks and spilling millions of gallons of oil, through its devastating aftermath.

Friday, July 8, 2022

The Real Price of Oil: When Externalities Become Transparent in Oil Documentaries

While Louisiana Story and Thunder Bay suggest that oil production will either leave the landscape untouched or benefit its ecosystem, films responding to major oil spills, including the March 24, 1989 Exxon Valdez eco-catastrophe in Alaska’s Prince Edward Sound, highlight the negative effects oil disasters may have on the environment and the cultures and economies it supports.

Monday, June 27, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence Conclusion

Once one of the shrimpers, Teche, learns that golden shrimp, shrimp that have eluded them for decades, are attracted to the rig, interdependence becomes possible. Martin shows Teche the golden shrimp off camera, so when Dominique and the townspeople arrive to take Francesca away, a symbiotic relationship between oilmen and shrimpers is established instead of the continuing conflict Dominique predicts. On camera, Martin tells Teche the golden shrimp foul up their intake valves at night and asks Teche what he might do for him. Teche declares, “What a dumb oil man,” but the ice has been broken and the battle between the shrimpers and oilmen is a short one.

Monday, June 20, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence, cont.

The myth of interdependence in Thunder Bay rests on an impossible link between oil and shrimp. When Gambi returns to the rig he and Martin fight, so Gambi nearly loses his job, and the rest of the crew nearly leaves the rig. But when Gambi hears about the financial situation, he brings the men back into their oilrig community, telling them, “We oughta have some of the glory for bringing in the first offshore rig.” Then men stay, and Gambi has married Francesca, building the first tangible bridge between oilmen and shrimpers, so after Martin goes in for supplies, he brings Francesca back for the first honeymoon on an oil rig.

Monday, June 13, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence, cont.

The climax of Thunder Bay occurs when Francesca’s fiancé Phillipe (Robert Monet) tries to blow up the rig, violently opposing oil drilling and causing Martin to think Stella is part of the plan. Martin stops the blasting, but fiancé Phillipe falls, and Martin can’t save him. Drilling continues despite this disaster, with a montage sequence illustrating progress. With eight days to go, however, Mac must pull out of the operation. The company would not finance the drilling, Mac explains, so Mac did, and he is out of money. Now the corporate board will no longer support the project, and it seems as if the shrimpers have won.

Monday, June 6, 2022

Thunder Bay and Myth of OIl/Sea Interdependence, Continued

Thunder Bay showcases an evolutionary argument that highlights a desire for a progress built on a rich past and, of course, on oil. Dominique remains unconvinced, however, and induces Mr. Parker (uncredited) from the Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to intervene with a cease and desist order for Martin and Gambi. When Dominique and Parker arrive with the order, Martin has already stopped the blasting, since they have chosen a drilling site.

Monday, May 30, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence

Ultimately, Thunder Bay reinforces Steve Martin’s position on offshore oil drilling. Martin effectively argues for the off-shore drilling by stressing interdependence, an organismic approach to ecology, claiming that oil and shrimp can not only mix but bring prosperity to all: “There’s oil down there,” Martin proclaims, and “this is going to be good for the town, good for the people.”

Monday, May 23, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence

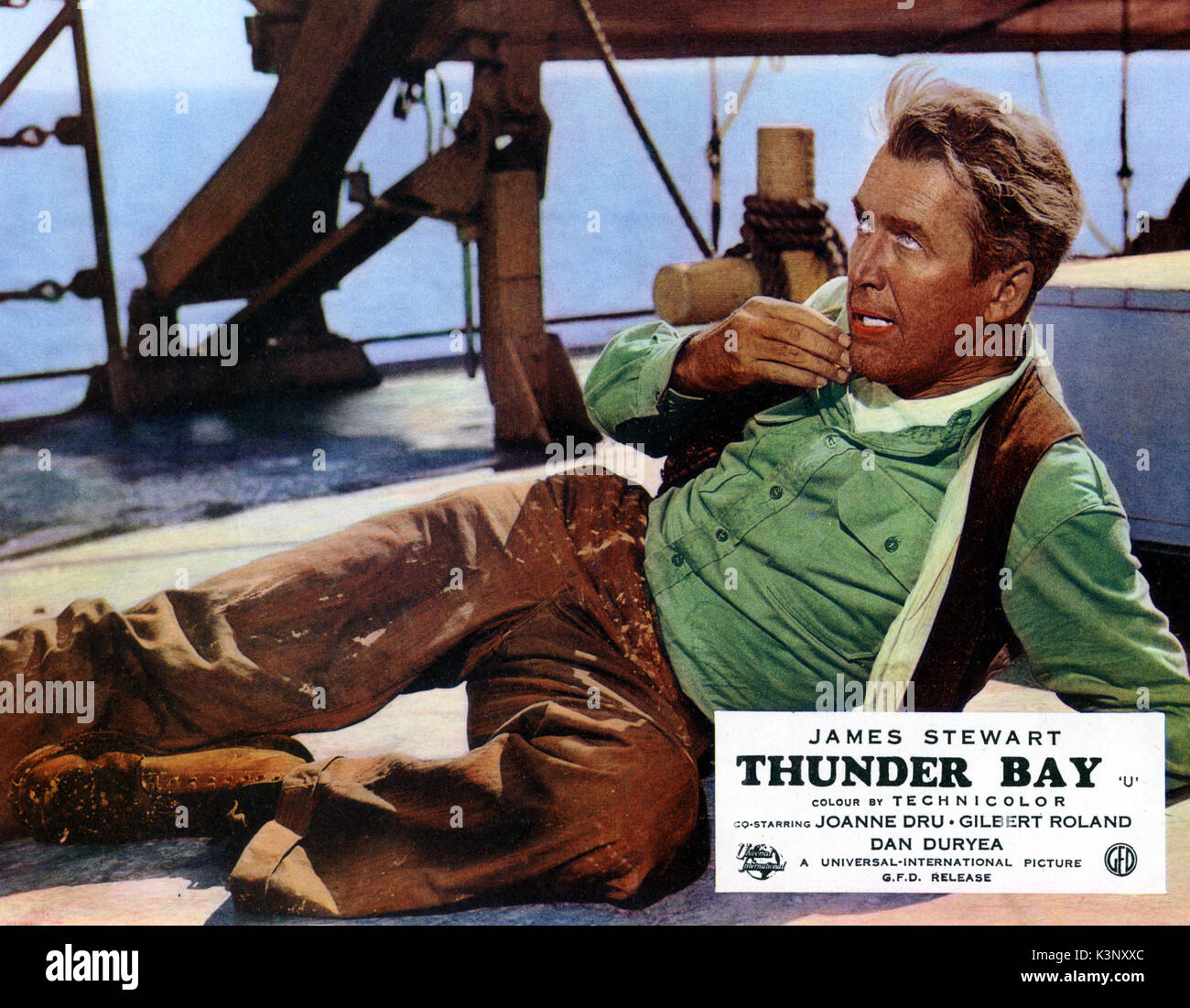

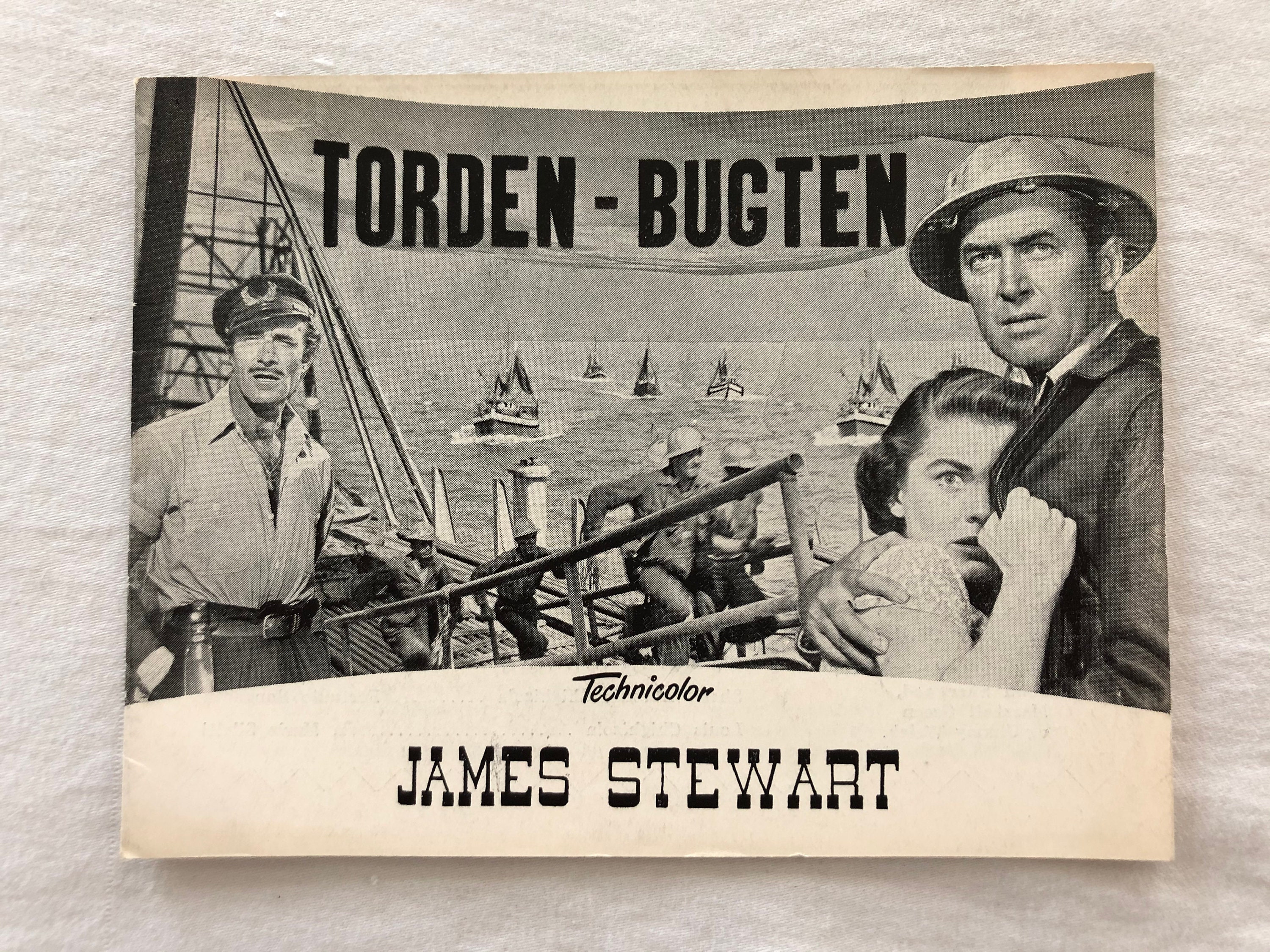

Set in 1946 Louisiana, Thunder Bay connects oil drilling and shrimping from its opening shot of Johnny Gambi and Steve Martin (James Stewart) walking down a long deserted road: They carry a heavy chest and discuss a money making idea that will require a $2 million investment, but then a Port Filliay Fish Company truck picks them up and takes them into town for a 2:00 appointment, aligning their oil drilling plan with the community’s fishing industry. The connection between fishing and oil drilling broached by the film is emphasized here, especially since, once they reach town, Gambi rents a shrimp boat for $50 a day, so the two can, they hope, form a partnership with a big oil man, Kermit MacDonald (Jay C. Flippen).

Monday, May 16, 2022

Thunder Bay and the Myth of Interdependence, continued

According to James Stewart biographer Jeanine Basinger, “Although it is somewhat unsettling today to watch a movie that sets a conflict between oil-drilling and nature—and oil-drilling is the hero—the machinery and the rig are photographed as things of beauty and majesty” (132) in Thunder Bay. From Basinger’s perspective, “Hard industrial grays and reds replace the greens and blues of nature and become the ‘colors’ of the modern era” (132). A. W. of The New York Times agrees, asserting that visually, “the complex off-shore drilling apparatus is the most distinctive aspect of Thunder Bay.” Shot in Technicolor and shown on an innovative “wide, curved screen [with] stereophonic [stereo] (or directional) sound” (A.W.) in the Loew’s State Theatre, Thunder Bay’s vast setting took center stage, overshadowing its weak narrative.

Monday, May 9, 2022

Anthony Mann's Thunder Bay (1953) and the Myth of Interdependence

Whereas Louisiana Story makes the case that an oil company can build its rig, drill for oil, build a pipeline and disappear, leaving the bayou untouched and the Cajuns around the well a little richer, Thunder Bay asserts that oil drillers and shrimpers can work together. In fact, in Thunder Bay, oil drilling provides more than jobs and money, according to the film. It provides access to “the golden shrimp” fishermen have been seeking for generations, stimulating a more productive shrimp season.

Monday, April 25, 2022

Louisiana Story and Oil Drilling Mythology, continued

Yet just as the alligator is ultimately killed in Louisiana Story, when the boy’s father intervenes, the oil drilling succeeds when, according to the film’s narrative, the boy helps, seemingly connecting the natural and supernatural with the culture of modernism represented by the oil rig and its men. The boy, still enraptured by the derrick, climbs it as if it were a Christmas tree, and tries dropping salt in the well for good luck, spitting on the salt for good measure. The oilmen laugh when he tells the oilmen, but while the boy is at home peeling potatoes later, he tells his family, “I know she won’t go away.” Then they hear the drill. According to an onscreen newspaper headline, “angling the hold to bypass the pressure area,” saved the well and brings the oil drillers success.

Monday, April 18, 2022

Louisiana Story and Oil Myths

After this long segment demonstrating the process of oil drilling, however, a scene in Louisiana Story shifts back to the boy and his raccoon in the bayou and, in a long sequence, highlights a battle between elements of nature. The boy leaves his raccoon and examines eggs left by an alligator. When the gator comes back on shore, the boy and we see the ‘gator eggs hatch. The boy holds a baby gator until the mother gator roars, and the boy runs away. The raccoon is now loose and swims up on a log, but the gator is close behind. The boy searches for his pet and passes representatives of wild nature: a spider in a web, a rabbit, a skunk, singing birds, and a deer.

Monday, April 11, 2022

Can Oil and Water Mix? Louisiana Story's take...

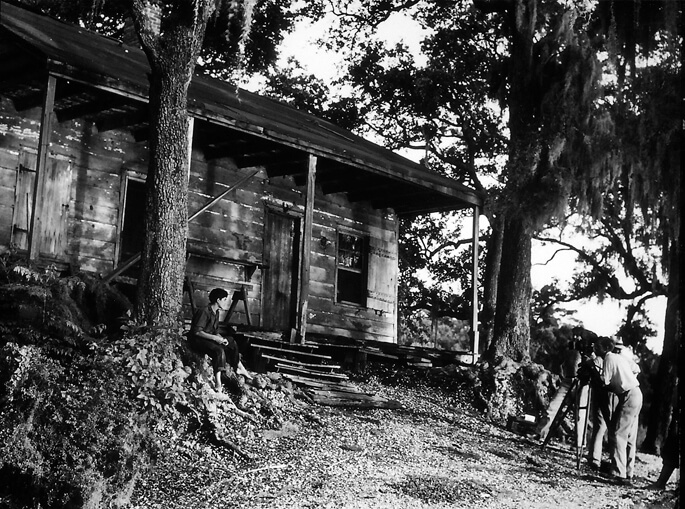

Although based in fantasy rather than reality, evidence in Louisiana Story suggests that nature and culture can and must remain separated. The oilmen, representing culture, leave the rustic cabin in their speedboat. Later the boy and his raccoon, representing nature, watch the oilmen from their rowboat as the drillers prepare to build their rig and platform. The boy fishes while Cajuns hunt along a pristine shore, further connecting them to the natural world. We get a view of homes on the shore from a houseboat, and a shore view of the motorboat and its wake. The boy and raccoon continue watching, and the wake of the motorboat throws him out of his boat, so he is literally connected with the natural world.

Monday, April 4, 2022

Myth of Separation between Oil and Nature in Louisiana Story

Despite clear evidence that oil drilling cannot leave the water and land around it untouched, the film and its reviewers assert the opposite, demonstrating through the experience of oil drillers and a Cajun boy that human and nonhuman nature can maintain separate existences and thrive. Instead of emphasizing the interdependent relationship between humans and the natural world, Louisiana Story suggests that to maintain the innocence of nature in the bayou, and of its more natural Cajun inhabitants, a humanity more aligned with culture and technology must leave wild nature behind, entering it only briefly and with caution to avoid an indelible affect. Two myths are perpetuated by the film, then: the myth that oil drilling can leave a natural setting untouched, and the myth that humans are somehow separate from nature rather than interconnected with it.

Monday, March 28, 2022

Louisiana Story and Separation Between Humans and the Natural World: Reviewers' Take

Contemporaneous reviews of the film support the claim that the film’s source of financing does not detract from its success as a work of art. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times asserts that the film “is not a submissive nod” to technology; yet, “it is recognition that the machine can be a useful friend of man, no more rapacious, in some way, than primitive man or nature themselves.” Crowther declares the scenes highlighting the oil drilling operation “the most powerful and truly eloquent phases” of Louisiana Story. Despite the sympathetic portrayal of the oil drillers, however, Crowther doubts money supplied by Standard Oil encouraged Flaherty’s perspective. Instead, Crowther asserts, “the ring of sincerity is clear in Flaherty’s film.”

Monday, March 21, 2022

Louisiana Story and Separation Between Humans and the Natural World: The Standard Oil Connection

The support for oil drilling and its benefits illustrated in Louisiana Story should come as no surprise because the Standard Oil Company financed the film. In his biography of Robert Flaherty, The Innocent Eye, Arthur Calder-Marshall asserts that Standard Oil began negotiating with Flaherty as early as 1944 for “a film dramatizing to the public the risk and difficulties of getting oil from beneath the earth” (211).

Monday, March 14, 2022

Approaches to Progress and Ecology in Louisiana Story and Thunder Bay

Although both films connect the oil industry with the environment, Robert Flaherty's Louisiana Story (1948) and Anthony Mann's Thunder Bay (1953) illustrate differing visions of oil drilling, visions that draw on conflicting views of both progress and ecology. Whereas Louisiana Story advocates for a progressivist vision of progress in which corporate “big guys” rather than local “innocent” Cajuns successfully reap the benefits of modernization and an economic or “fair use” approach to ecology, Thunder Bay demonstrates a populist view of progress and an organismic or “wise use” approach to ecology. Yet both films’ representations rest on fabricated American myths, which fall flat under scrutiny.

Monday, March 7, 2022

Oil Films and/or Interdependence

Filmic representations following Kerr-McGee’s success draw on a drive to minimize the conflict between the fishing and oil industries and valorize oil drilling and the opportunities it brings. Both Robert Flaherty’s Louisiana Story (1948) and Anthony Mann’s Thunder Bay (1953), for example, commend the oil industry for bringing wealth to an otherwise impoverished region, with differing levels of interdependence between local residents and oil company outsiders on display.

Monday, February 28, 2022

The Search for the “Golden Shrimp”: The Myth of Interdependence in Oil Drilling Films

According to John Ezell’s Innovations in Energy: The Story of Kerr-McGee, after the first successful oil well was drilled out of sight of land in the Gulf of Mexico in 1947 by the Kerr-McGee Company, the January 1948 issue of Oil declared, “The Kerr-McGee well definitely extends the kingdom of oil into a new province that is of incalculable extent and may help assuage the all-devouring demand for gasoline and fuel oils” (quoted in Ezell 169). A reporter from the Kermac News illustrated this valorization of the success of the oil well: “Everybody shook hands with everybody twice” (quoted in Ezell 164-5).

Completion of British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon oil rig in 2009 resulted in similar kudos. As the deepest oil and gas well ever drilled offshore, the Deepwater Horizon was lauded by Robert L. Long, Transocean Ltd.'s Chief Executive Officer. On Vermont Public Radio, Debbie Elliot asserted the same positive response to oil drilling in the Gulf. But according to Elliot, fishermen and oil companies built an interdependent relationship: “The local fishermen feared their way of life was in jeopardy when the first oilmen arrived in Cajun south Louisiana. But over the last half century, the two industries learned to live together. Oil and gas brought jobs and opportunity for many families.”

It is this interdependent relationship between the fishing and oil industries that has taken center stage in media discussions after the Gulf of Mexico Deepwater oil rig explosion and spill in April 2010, in spite of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster that seemed to demonstrate oil and wild nature don’t mix. From a contemporary perspective, the conflict between these two industries seems new, a product of the rig explosion and its aftermath. In fact, the conflict began with the first oil well in and around the Gulf in the 1910s, culminating with the Kerr-McGee’s successful well in 1947. Any conflict between the two industries, however, has been whitewashed by media representations of their relationship, building toward Elliot’s conclusion that they learned to live together because oil brought money and jobs. Oil films reflect this myth.

Monday, February 21, 2022

O Illinois!

Monday, February 14, 2022

Quantum of Solace and Water Wars

After Bond and Camille escape by plane and parachute into Greene’s Bolivian eco-park, they find evidence for the real reason for Greene’s establishing nature preserves: “They used dynamite,” Bond exclaims. “This used to be a riverbed. Greene isn’t after the oil. He wants the water…. It’s one dam. He’s creating drought. He’ll have built others.” With control of water, Greene and Quantum, the clandestine company he fronts can charge exorbitant prices for the resource.

Monday, February 7, 2022

Quantum of Solace and Water Rights, continued

For Clover, Quantum of Solace “comes closer to telling the Bolivian story than the critics were able to address, or notice” (8). With the devastating repercussions of privatization, the citizens of Cochabamba revolted, so that “midway through 2000, the “Bolivian Water Wars” ended with the eviction of the consortium and, shortly, the fall of the government itself” (8), paving the way for the election of Evo Moralis and his Movement for Socialism. Vandana Shiva sees the outcome of this water war as a great victory for “the people’s democratic will” and proof that “privatization is not inevitable, and that corporate takeover of vital resources can be prevented” (103).