To document the effects of such an evolutionary nightmare, Darwin’s Nightmare opens and closes on views of the European cargo planes landing in and leaving Tanzania, all piloted by white European men who look well-fed in contrast to Tanzanians pulling an out-of-control cart full of perch in the impoverished town or fishing on Lake Victoria, the source of the Nile and birthplace of civilization. Both fishermen and the boys pulling the cart take them to the factory, explains Marcus, a police officer. The film also shows us how both fishermen and boys suffer because their source of food has become a commodity. Fishermen and their families starve. Some fishermen die on the lake, leaving wives and children to mourn them. Many children end up orphaned and living on the street, fighting over scraps of food and falling into a drug-induced sleep on sidewalks and in doorways.

Women in this colonized community are left with few choices. After their husbands die of AIDS, fishing accidents, or war, they care for their children until they starve to death, die from fumes exuded by smoking perch corpses, or sell themselves to the European cargo pilots. They may then live in brothels and bars constructed for their colonizers where they sometimes die at the hands of their so-called benefactors, as does Eliza, a beautiful young woman highlighted in the film. The lone fish factory employs only 4000 people and pays as little as possible—a dollar a day for a night guard, for example.

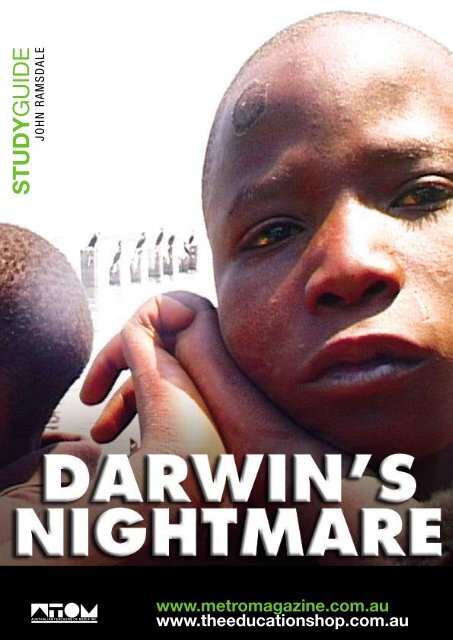

The film personalizes each of these struggles: It foregrounds Eliza’s attempts to figure out her life, her glowing smile, and her powerful voice singing her country’s anthem, “Tanzania.” It also focuses on Raphael, a night guard fearing for his life, since the previous guard had been murdered, Jonathan, a painter who documents the life on the streets he left behind, the group of boys fighting to survive on the street, and the cargo pilots themselves, some even regretting their part in the arms sales that contribute to so many deaths.

Director Hubert Sauper suggests that Darwin’s Nightmare stands as evidence that “The old question, which social and political structure is the best for the world seems to have been answered. Capitalism has won.” For Sauper, the changes in the communities around Lake Victoria are evolutionary and demonstrate that “the ultimate forms for future societies are ‘consumer democracies,’ which are seen as ‘civilized’ and ‘good.’ In a Darwinian sense, the ‘good system’ won. It won by either convincing its enemies or eliminating them.”

According to Sauper,

In Darwin’s Nightmare, "I tried to transform the bizarre success story of a fish and the ephemeral boom around this "fittest" animal into an ironic, frightening allegory for what is called the New World Order. …It is, for example, incredible that wherever prime raw material is discovered, the locals die in misery, their sons become soldiers, and their daughters are turned into servants and whores…The arrogance of rich countries towards the Third World (that's three quarters of humanity) is creating immeasurable future dangers for all peoples."