Despite clear evidence that oil drilling cannot leave the water and land around it untouched, the film and its reviewers assert the opposite, demonstrating through the experience of oil drillers and a Cajun boy that human and nonhuman nature can maintain separate existences and thrive. Instead of emphasizing the interdependent relationship between humans and the natural world, Louisiana Story suggests that to maintain the innocence of nature in the bayou, and of its more natural Cajun inhabitants, a humanity more aligned with culture and technology must leave wild nature behind, entering it only briefly and with caution to avoid an indelible affect. Two myths are perpetuated by the film, then: the myth that oil drilling can leave a natural setting untouched, and the myth that humans are somehow separate from nature rather than interconnected with it.

Louisiana Story perpetuates these two myths through both its aesthetic and its narrative. Close-ups of a pristine bayou open Louisiana Story. Flowers, an alligator, and a heron on an evergreen tree emphasize the film’s naturalistic setting. A lone boy poles through weeping cypress trees in a small boat. We see the bayou from his point of view, including water below him. A narrator describes the scene, even mentioning werewolves to set the mythic tone of this innocent scene. The boy wears salt on his waist and something inside his shirt to protect him from all that bubbles, we are told and smiles at a raccoon in a tree, connecting him to both natural and supernatural elements. A snake, gators, and grasses blowing in the wind continue the scene.

When the boy shoots at an animal, and the pristine scene is disrupted, the conflicting element in the film is introduced: modernism in the shape of oil drilling in the bayou. Other explosions take the gunshot’s place, then, as wheeled machinery drive up into the bayou. The machine looks like a tractor, a cultivator cutting a path through the grass. The boy floats away, demonstrating the separation between culture and nature the film perpetuates.

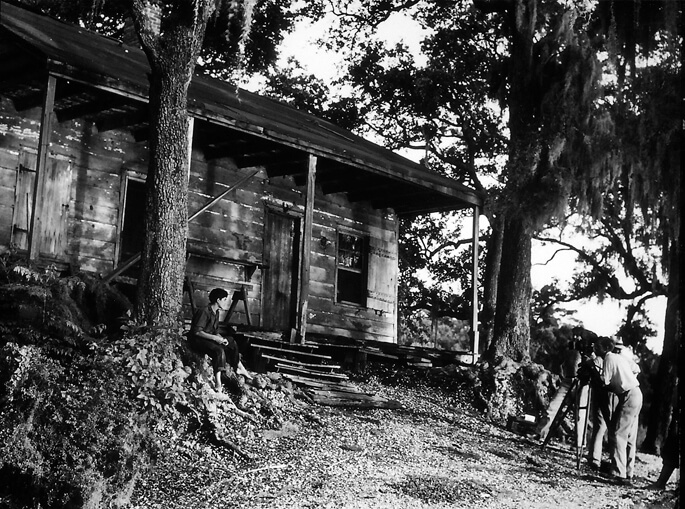

The boy and his Cajun family represent an innocence that is untouched by civilization. When the boy heads home to his Cajun family, a family structure more in touch with the natural world is introduced. Their cabin sits beside the bayou and can only be accessed by boat. Inside the cabin, the boy’s father talks about “gators” in a Cajun accent to a lean cut younger man, reinforcing his connection to nature. The boy’s mother does offer coffee, a connection with culture, but the boy’s entrance by boat at his parent’s dock again highlights how isolated this family is from society.

The blasting that continues, however, contrasts and conflicts with this innocent, more “natural” scene, highlighting the intervention on display. Modern culture has entered the pristine wilderness of the bayou and infiltrated the innocent Cajun family that is still tied to the natural world. To seal this connection, the oil drillers offer lease agreements to the boy’s father: “Can that thing really tell where oil is?” the older man asks, but he signs his name to a contract.

No comments:

Post a Comment