The wall and gates, however, limit this garden to only the rich white colonizers and lock out Fausta’s indigenous family members and their impoverished community. As if responding to this exploitation, Fausta’s nose bleeds when she encounters her mistress Aida. In her servant’s alcove, she sings to hide her fear as she cuts off potato growth. The estate garden seems to usurp her own inner garden in this scene. Yet, when Fausta encounters and joins forces with the estate gardener, Noé (Efraín Solís), she discovers a way to bridge her community’s constructed garden and her own inner garden with the fecundity of Aida’s oasis. An initial connection occurs when shots of a colorful wedding in the desolate Lima hills are juxtaposed with images of a shattered piano disrupting Aida’s garden. In Lima’s desolate landscape, ornate clothing and violet tents transform into flowers erupting out of the desert. But Aida’s paradise is disrupted by the broken piano thrust from a window into the foliage below. In both scenes, the garden and machine merge, highlighting the similarity between the two spaces.

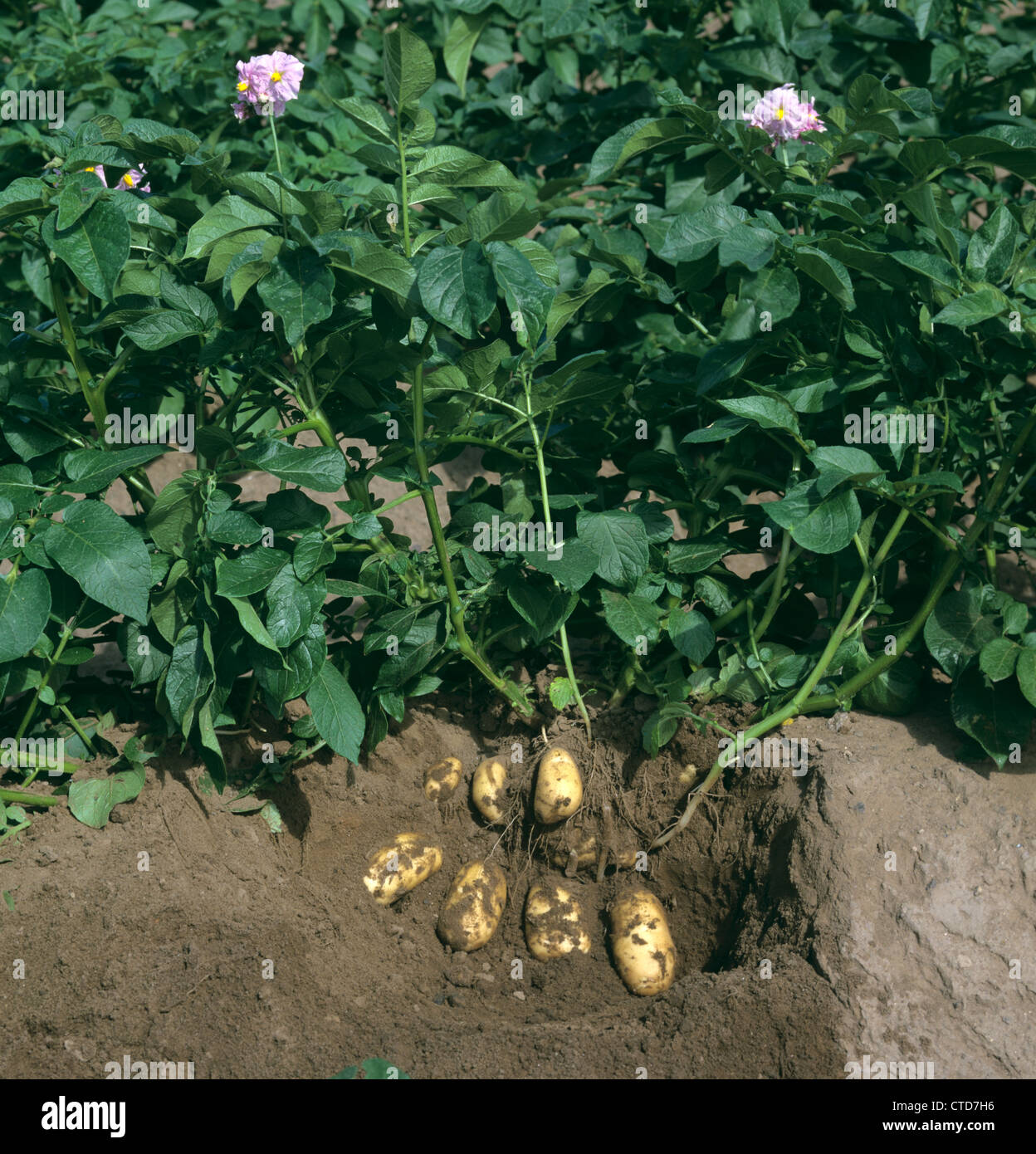

But it is Fausta’s relationship with Noé that moves her to a middle place that allows both human and nonhuman nature to blossom. Aida and her garden highlight the war and exploitation Fausta and her mother attempt to escape in Lima. Fausta’s uncle’s family shows us an artificial garden built for the colonized. But Noé and Fausta integrate nonhuman nature in the wasteland outside Aida’s walls. Although Aida claims watering her garden “calms her,” she exploits Fausta, stealing her mermaid song and breaking a promise to give Fausta the pearls they collect from a broken necklace. She remains locked away, even throwing Fausta out of her car after a concert. Noé on the other hand, offers her comfort and security, not only by escorting her home (from a distance) but by teaching her to cultivate plants, a skill she gained first from a village vegetable garden before their forced move to Lima. As Noé explains, “plants tell the truth about people,” and the flowers she chooses tell him she needs comforting. Together they burn the piano, as if resisting the machine. And instead of “bleeding roses” from her nose, Fausta holds a gardenia in her mouth. When she asks him why he plants everything but potatoes in the garden, Noé explains that potatoes are cheap and flourish little.

When Fausta finally begs to have the potato removed, she and Noé gain access to that more verdant middle place. After stealing back the pearls she earned, Fausta faints at the estate gate where Noé finds her and carries her to the clinic for the removal. With the pearls in her possession, Fausta can transport her mother away from Lima and reunite her with the natural world she was forced to leave behind. In a dramatic turn, Fausta carries her mother across a beach and leaves her close to the ocean where she sings as the sea takes her mother home. Fausta has now become part of a larger biotic community, a middle place where thriving traditional parks, bright-colored constructed gardens, and her own potato can thrive. As a symbol of this middle place, Noé leaves a flower on her porch, a blooming potato plant.