Representations of future cities in

fictional films usually emphasize spectacle, power, and divisions rather than

interdependent relationships with the natural world and each other. Fictional

films released after 2010, six years after Day

After Tomorrow (2004) and ten years after the Age of the Anthropocene was

popularized primarily highlight dystopic visions of the future. What struck us,

however, is how little these films addressed environmental issues, including

climate change. Although we explored cli-fi (climate fiction) films in our Monstrous Nature: Film, Environment, Horror

(2016), few films addressing the future ramifications of climate change are set

in future cites, and Star Trek Into

Darkness (2013) moves beyond dystopic views of the city of the future

without referencing environmental issues at all.

In many fictional films, the utopian

city is available only for the affluent and powerful few. In The Hunger Games (2012) and its sequels

(2013, 2014, 2015), the twelve districts outside of the Capitol of Panem

struggle to meet their own survival needs after providing resources for the

greedy citizens of the Capitol. The brief CGI-enhanced establishing shots of

the Capitol reveal a technologically advanced utopia for the chosen few.

District Twelve, home of the films’ protagonist Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer

Lawrence), however, gives so much coal to the Capitol that it can’t adequately

heat its homes. Food is so scarce that Katniss and her family can only survive

by illegally hunting outside the district’s fence. District Thirteen fares even

worse, since after they rebelled, their village was destroyed, forcing

survivors into an underground bunker where they must ration food and share

living space.

Like The Hunger Games, Elysium (2013) separates rich and

powerful from the poor providing their resources, but in Elysium a population

explosion has created a global slum on Earth, forcing the privileged to build

their utopian city above ground in a sky city. The Congress (2013) offers utopian urban visions only in an

animated world that drug-addicted residents create for themselves. In the

non-animated “real” world, animated heroes are revealed to be homeless and

despairing victims. Only those living in large airships above the slums below

provide hope in this dystopic future. The Neo-Seoul segment of Cloud Atlas (2012) highlights technology

and genetic engineering in a Vice City.

The Zero Theorem (2013) offers a dystopian Terry Gilliam vision like that

of Brazil (1985).

Divergent

(2014) also stresses divisions established to resolve conflicts that nearly

destroyed humanity. After a great war, society was divided into five separate

areas called factions to maintain order in a future Chicago: Erudite, Amity, Candor,

Dauntless, and Abnegation. Those who do not fit any of the five categories are

labeled divergent and may be exiled from the community. Although the factions

seem balanced at the beginning of the film, the Erudite faction seeks the same

power and privilege of the Capitol citizens of The Hunger Games. These series of films also illustrate

evolutionary myths under the city and urban eco-trauma. The underworld of

District Thirteen in Hunger Games and

The Pit, home of the Dauntless faction, in Divergent

highlight how the underground city evolves in post-apocalyptic film. Eco-traumas

are played out in the Hunger Games themselves, as well as in the Districts

outside of the Capitol in The Hunger

Games films. In Divergent, the Erudite faction forces

Dauntless soldiers to attack Abnegation and slaughter divergent citizens who

can’t be as easily controlled.

While Divergent shows us a post-apocalyptic Chicago where overhead shots

reveal paved streets and parking lots broken by weeds, Star Trek Into Darkness offers more utopian views of London and San

Francisco. According to Visual Effects Supervisor Roger Guyett, “Our philosophy

about doing cities, and respecting the canon of how the work is described by

Gene Roddenberry, is that you’re only a few 100 years in the future.” Instead

of depicting a post-apocalyptic future, Guyett highlights how technological

advancements may enhance the landmarks and architecture of San Francisco and

London, including landmarks such as St. Paul’s Cathedral and the River Thames.

According to Guyett, "We even went to London and took

a lot of pictures from different angles, to try to maintain the real geography

of it. But, at the same time, we want to elaborate on that and use our

imagination on how that might have changed."

Star

Trek Into Darkness promotes a more utopian vision of the city that suggests

humanity can adapt and live more sustainably 100 years from now. Although the film

does not explicitly address environmental issues, it demonstrates how

technology might allow humanity to live interdependently with the natural

world. Big Hero 6

(2014) also suggests technology can address racial, economic, and, perhaps,

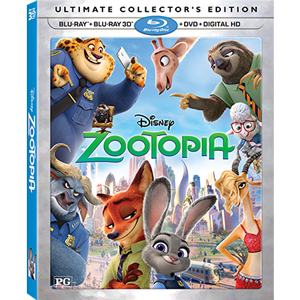

environmental conflicts in a Disneyfied fictional and animated San Fransokyo. None of these films go as far as Zootopia or Tomorrowland or the documentaries Under the Dome and The Absent House.