Ecocinema and the City seeks to add to urban ecocinema

scholarship by exploring four sections arranged to highlight the increasing

importance nature performs in the city: Evolutionary Myths Under the City,

Urban Eco-Trauma, Urban Nature and Interdependence, and The Sustainable

City. The first two sections,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City” and “Urban Eco-Trauma,” take more

traditional ecocinema approaches and emphasize the city as a dangerous

constructed space.

Part I,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City” examines evolutionary narratives of

environmental adaptation in both film noir and documentaries focused on urban

sewers and subways. The films explored in our first section, “Evolutionary

Myths Under the City,” call into question the idea of the city as natural and

unaffected by human intervention and illustrate how social and environmental

injustices sometimes intertwine. The notion of displacement from the New

Objectivity art movement of the 1920s helps elucidate this de-naturalizing of

the city. As Daniela Fabricius explains, “Displacement can be a way of

understanding not only the abyss between a landscape and how it is represented

but also the erosion of the seemingly fixed binaries that separate natural and

manmade environments” (175). “Evolutionary Myths Under the City” explores these

fluid binaries as it focuses on tragic and comic evolutionary narratives. The

films explored in this section ask evolutionary questions about who we are,

where we’re going, and which story of ourselves we choose to construct: a

tragic or comic evolutionary narrative.

Chapter 1, “The

City, The Sewers, The Underground: Reconstructing Urban Space in Film Noir”

examines the idea of the city as a social and cultural construct through a reading

of He Walked by Night (1948). The

film highlights how and why not genetics but social, cultural and historical

forces construct “gangsters.” But what sets the film apart from other noir

films is the attention it gives to the urban infrastructure hidden below its

progressive construction. By foregrounding sewers as constructions, escape

routes, and seemingly safe havens for noir characters, the film demystifies what seem like “givens” and

calls into question the idea of the city as natural.

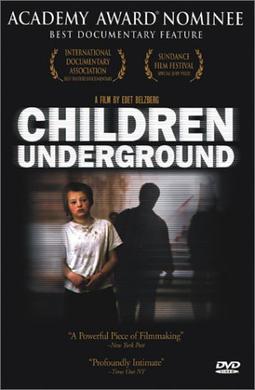

Chapter 2, “Documenting

Environmental Adaptation Under the City: Children

Underground (2001)” explores underground constructions from the perspective

of homeless children in Children

Underground (2001). On the surface the children in Children Underground have entered an underground that serves as the

site of technological progress where excavation produces not only the means of

production—coal and oil, for example—but also the foundation for the urban

infrastructure—sewage and water systems, railways, gas, and lines for

electricity, computers, and phones. They have entered a technology-driven

underworld and reconstructed, domesticated, and humanized it as a home, an

ecology in which they can move beyond survival toward interdependence. Yet

because their plight and the home they inhabit are built on both nature and former

dictator Ceausescu’s cultural attitudes, these homeless children also

illustrate how social and environmental injustices sometimes intertwine.

No comments:

Post a Comment