This blog explores popular film and media and their relationship to the environment.

Monday, February 26, 2018

Sunday, February 25, 2018

Ecocinema and the City Part I

Ecocinema and the City seeks to add to urban ecocinema

scholarship by exploring four sections arranged to highlight the increasing

importance nature performs in the city: Evolutionary Myths Under the City,

Urban Eco-Trauma, Urban Nature and Interdependence, and The Sustainable

City. The first two sections,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City” and “Urban Eco-Trauma,” take more

traditional ecocinema approaches and emphasize the city as a dangerous

constructed space.

Part I,

“Evolutionary Myths Under the City” examines evolutionary narratives of

environmental adaptation in both film noir and documentaries focused on urban

sewers and subways. The films explored in our first section, “Evolutionary

Myths Under the City,” call into question the idea of the city as natural and

unaffected by human intervention and illustrate how social and environmental

injustices sometimes intertwine. The notion of displacement from the New

Objectivity art movement of the 1920s helps elucidate this de-naturalizing of

the city. As Daniela Fabricius explains, “Displacement can be a way of

understanding not only the abyss between a landscape and how it is represented

but also the erosion of the seemingly fixed binaries that separate natural and

manmade environments” (175). “Evolutionary Myths Under the City” explores these

fluid binaries as it focuses on tragic and comic evolutionary narratives. The

films explored in this section ask evolutionary questions about who we are,

where we’re going, and which story of ourselves we choose to construct: a

tragic or comic evolutionary narrative.

Chapter 1, “The

City, The Sewers, The Underground: Reconstructing Urban Space in Film Noir”

examines the idea of the city as a social and cultural construct through a reading

of He Walked by Night (1948). The

film highlights how and why not genetics but social, cultural and historical

forces construct “gangsters.” But what sets the film apart from other noir

films is the attention it gives to the urban infrastructure hidden below its

progressive construction. By foregrounding sewers as constructions, escape

routes, and seemingly safe havens for noir characters, the film demystifies what seem like “givens” and

calls into question the idea of the city as natural.

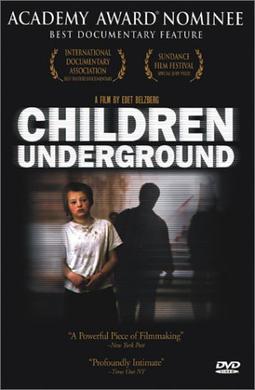

Chapter 2, “Documenting

Environmental Adaptation Under the City: Children

Underground (2001)” explores underground constructions from the perspective

of homeless children in Children

Underground (2001). On the surface the children in Children Underground have entered an underground that serves as the

site of technological progress where excavation produces not only the means of

production—coal and oil, for example—but also the foundation for the urban

infrastructure—sewage and water systems, railways, gas, and lines for

electricity, computers, and phones. They have entered a technology-driven

underworld and reconstructed, domesticated, and humanized it as a home, an

ecology in which they can move beyond survival toward interdependence. Yet

because their plight and the home they inhabit are built on both nature and former

dictator Ceausescu’s cultural attitudes, these homeless children also

illustrate how social and environmental injustices sometimes intertwine.

Urban Cinema Studies and the Search for Everyday Environments

Explorations of

urban cinema sometimes emphasize the interconnection between cinema and a

(sometimes) lifeless modern and post-modern city, opening up possibilities for

ecocritical readings. In the introductory essay to Cinema and the City: Film and Urban Societies in a Global Context, for

example, Mark Shiel highlights the “curious and telling correlation between the

mobility and visual and aural sensations of the city and the mobility and

visual and aural sensations of the cinema” (1). The film industry contributes

to urban economies around the world “in the production, distribution, and

exhibition of motion pictures, and in the cultural geographies of certain

cities particularly marked by cinema (from Los Angeles to Paris to Bombay)

whose built environment and civic identity are both significantly constituted

by film industry and film” (1-2).

Shiel suggests

urban cinema’s grounding in the society of the city and the culture of cinema

opens it up for interdisciplinary readings connecting film studies with

sociology, cultural studies, geography, and urban studies. The book’s goal is

to “produce a sociology of the cinema in the sense of a sociology of motion

picture production, distribution, exhibition, and consumption, with a specific

focus on the role of cinema in the physical, social, cultural, and economic

development of cities” (3). Both sociology and film studies gain much from this

connection, according to Shiel. Following an Althusserian structural view,

Shiel argues Cinema and the City “recognizes

the interpenetration of culture [film], society [city], and economics as part

of ‘a whole and connected social material process,’ to use Raymond Williams’s

terminology” (4). For Shiel, cinema is also “a peculiarly spatial form of

culture” (5) in a global (inequitable) context that is historically situated.

Instead of approaching cinema and the city from an architectural perspective,

this volume explores the connections between the culture of cinema and the

society and economics of the city.

Focused

exclusively on Indian cinema, Preben Kaarsholm’s edited volume

Like Shiel,

Kaarsholm agrees that modernity and the metropolis are intertwined and

interrelated, and that association produces both positive and negative results.

As Kaarsholm suggests, “modernities and experiences of the breakdown of the old

come to the fore in the plural—as historical conjunctures and life situations

which are the outcomes of a single evolutionary logic, but rather as

battlefields of contestations between different forces of development and

different cultural and political agendas” (5), especially those between

European colonial powers with linear and dualist views of progress and an

indigenous agenda that strives for a more communal and equitable vision of

modernity. Indian cinema reflects this same mixture of Westernized and

indigenous cultures, both in films produced for Indian audiences and those

directed at an international audience and screening circuit (9).

With their

emphasis on class, race, and cultural politics, Shiel and Kaarsholm highlight

issues with potential environmental concerns, including environmental justice

and environmental racism. They also begin to connect the economic concerns

illustrated by urban cinema with toxic environments and human ecology. The hope

is that works like these can also reveal not only the toxic connections between

“cultural and political agendas” and the environment, but also demonstrate “the

fundamental connections to the environment in our everyday lives” (Price 538).

Sunday, February 11, 2018

Central Illinois Feminist Film Festival

Central Illinois Feminist Film Festival

Eastern Illinois University

Call for Submissions

Deadline: March 1, 2018

Festival: March 20, 2018

We are looking for short student films of high artistic quality that satisfy at least two of the following criteria:

1. Films created with an emphasis on gender and/or social justice issues

2. Films that link local and global issues

3. Films created by people underrepresented in the media field (women, people of color,

queer/transgendered people, people with disabilities)

4. Films made by people from the Central Illinois area

How to submit:

· Submit through Film Freeeway: https://filmfreeway.com/festival/CIFFF

· Send a link to your Vimeo, YouTube, or other source to rlmurray@eiu.edu

Guidelines:

1. Films should be short: under 30 minutes in length.

2. Films should be labeled with your name, address, and email address, and

the title of your film.

3. In your cover letter, explain how you and your film fit our criteria and include a two-three sentence synopsis.

Note: There is no submission fee for this film festival.

This film festival promotes the mission of our Women’s Studies Program: to promote an understanding of how issues related to gender, age, race, economic status, sexual identity, and nationality affect women's lives and the communities in which they live. In order to promote an equitable and sensitive environment for all persons, Women’s Studies also responds to issues affecting women on campus and in the community.

Send Queries to: Central Illinois Feminist Film Festival

Women’s Studies Program, Eastern Illinois University, Charleston, IL 61920

Attn: Robin L. Murray

Thanks to UC Davis Film Fest for information regarding the Call

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)