The same thematic and aesthetic philosophy underpinning UPA’s Gerald McBoing Boing guides 1001 Arabian Nights. Gerald McBoing Boing has clear connections to Mr. Magoo, the protagonist of 1001 Arabian Nights. According to Don Markstein’s Toonpedia, for example, when Mr. Magoo was included in Dell Comic Books, he shared most of the production space with Gerald McBoing Boing. Markstein explains that UPA introduced Mr. Magoo in Ragtime Bear, a theatrical release, “when, in 1948, Columbia Pictures decided to fold its in-house animation studio and hire the fledgling outfit instead.” Although Markstein asserts that there was no one creator for the Mr. Magoo character, he attributes the character to Millard Kaufman, the scriptwriter; John Hubley, the director; and Jim Backus, the actor who voiced Magoo until his death in 1989. According to Markstein, “Backus was encouraged to ad-lib in his depiction of the crotchety old coot, and to ham it up to his heart’s content. A great deal of the final product represents his off-the-cuff creativity.”

That off-the-cuff creativity contributed to Magoo’s success as a bumbling virtually blind character, but, according to Barrier, “what made Magoo more pitiable was the way his nearsightedness magnified his personality” (521). As John Hubley explains, “A great deal in the original character, the strength of him, was the fact that he was so damn bull-headed. It wasn’t just that he couldn’t see very well; even if he had been able to see, he still would have made dumb mistakes, ‘cause he was such a bull-headed opinionated old guy” (quoted in Barrier 521).

Such a focus on blindness as a personality trait highlights both narrative and aesthetic elements that link Magoo with Gerald McBoing Boing. Wells asserts that Magoo’s character’s “whole agenda is concerned with perceived reality” (Animation and America 66), an agenda produced by the 1950s context in which he and UPA were placed. That same agenda drives Gerald McBoing Boing, a character with another sense distortion that builds his personality. As David Fisher explains in 1953, “Mr. Magoo represents for us the man who would be responsible and serious in a world that seems insane; he is a creation of the 1950s, the age of anxiety; his situation reflects our own” (quoted in Wells Animation and America 66). Note also that both Magoo and Gerald are people, not animals, the most prominent characters in Disney, MGM, and WB cartoons.

Magoo’s character was connected to its modernist context in philosophical and aesthetic ways, as well. As Wells suggests, Magoo’s “shortsightedness and irritability” were more an “inability to see” that required “a philosophical approach to perception, and to the possibilities of syn-aesthetic cinema, and ways of ‘post-styling’ the reality of both the real world and the Disneyesque orthodoxy” (Animation and America67). John Hubley embraced this aesthetic. In an interview, Hubley explained the central premise of his work as “an image that plays dramatically (a visual metaphor) and will develop into a scene” (quoted in Wells Animation and America 67). According to Wells, this image “aspires to the work of modernists like Picasso, Dufy, and Matisse, while also embracing the freedom of jazz idioms” (Animation and America 67).

Although Hubley did not direct 1001 Arabian Nights, his imprint remained embedded on Mr. Magoo’s character and contributed to its view of nature and a technology-driven culture as not only interdependent but indelibly connected. In fact, in 1001 Arabian Nights technology plays a vital role in building not only the stylized aesthetic, but also in driving a narrative in which Magoo’s bumbling character assists his hapless son only because technology intercedes.

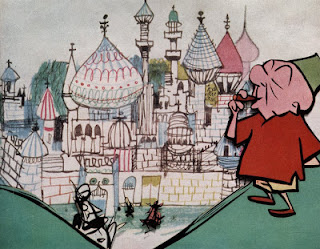

1001 Arabian Nights became UPA’s first animated feature because financial support wasn’t available for their original idea, producing Don Quixote with Magoo as Quixote. According to Jules Engel, one UPA’s principle players, “We had Aldous Huxley in to write a script for that. He did about a thirty-page skeleton script, but the bank wouldn’t buy it. They had never heard of Don Quixote, but they had heard of Arabian Nights, so we got money for Arabian Nights (quoted in Maltin 335). Because Pete Burness left the studio, UPA hired Jack Kinney, a Disney veteran, to direct and his brother Dick to write the story. Robert Dranko supervised the production design (Maltin 335). Although critics found fault with the film’s narrative and the relevance of Magoo’s character, most, like Maltin, agree that it “boasted sophisticated design and color” (335). Hal Erickson agrees and notes that “Many of the character designs seen in Arabian Nights were reused on UPA’s weekly 1964 TV series The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo.”

For us, that sophisticated design and color augments a narrative in which the technology of a genie in his bottle, a flying carpet, and a magic flame supersede bumbling and incompetent human and nonhuman nature. Yet technology does not serve as a tool for destruction in 1001 Arabian Nights. Instead, it serves to preserve and protect humans and their natural world and illustrates the interconnected interdependence between culture and the nature of humanity, and a technologically-driven aesthetic demonstrates the interconnectedness between technology and human nature throughout the film.

A modernist aesthetic connects with a modernist worldview in both the Sultan’s and the Wazir’s settings. The red, hot pink, and orange background sets off the midnight blue of the Wazir and his secret passage and chambers when he prepares to meet the Princess. The red-robed Sultan and pink and blue clad princess contrast with this dark Wazir. This modernist aesthetic continues into settings that foreground Aladdin and Jasminde’s infatuation. Ultimately it is supernatural technology that connects Aladdin and Jasminde: a magic lamp, a flying carpet, and a bumbling Mr. Magoo.

No comments:

Post a Comment