New Farms, Big Success: With Three Rock Star Farmers (2015) takes a proposal approach to sustainable farming practices, this time with emphasis on farmers in the USA and Canada. Although the general overview of the problems associated with agribusiness is brief, each of three sections introduces solutions that address some of the same issues discussed in Voices of Transition. Environmentalist Bill McKibben establishes the film’s purpose: finding viable agricultural practices that address issues surrounding climate change. According to McKibben, climate change may have horrific effects on agriculture, depleting arable soil and discouraging biodiversity. New farming practices are necessary to combat these changes and address environmental disasters associated with agribusiness.

The first sequence highlights the work of Essex farmer Kristin Kimball, author of The Dirty Life. Her farm in Essex, New York stresses the kind of mixed farming approach discussed in Voices of Transition. Kristin raises grass-fed beef, pork, and chickens that provide fertilizer for 50-60 varieties of vegetables, fruits, and grains for bread. Her farm relies on solar energy and works toward economic, environmental, and social sustainability. Draft horses pull a cultivator from the 1930s, eliminating the need for coal or gasoline. By rotating her 500 acres of crops, Kristin solves problems such as potato beetle infestations. Only organic pesticides are used. Even chicken coops are moved every day to fertilize fields for hay. As the director of a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) cooperative, Kristin provides consumers with produce once a week instead of following what she calls “a drug dealer model” like that of agribusiness. She emits less carbon and produces better food.

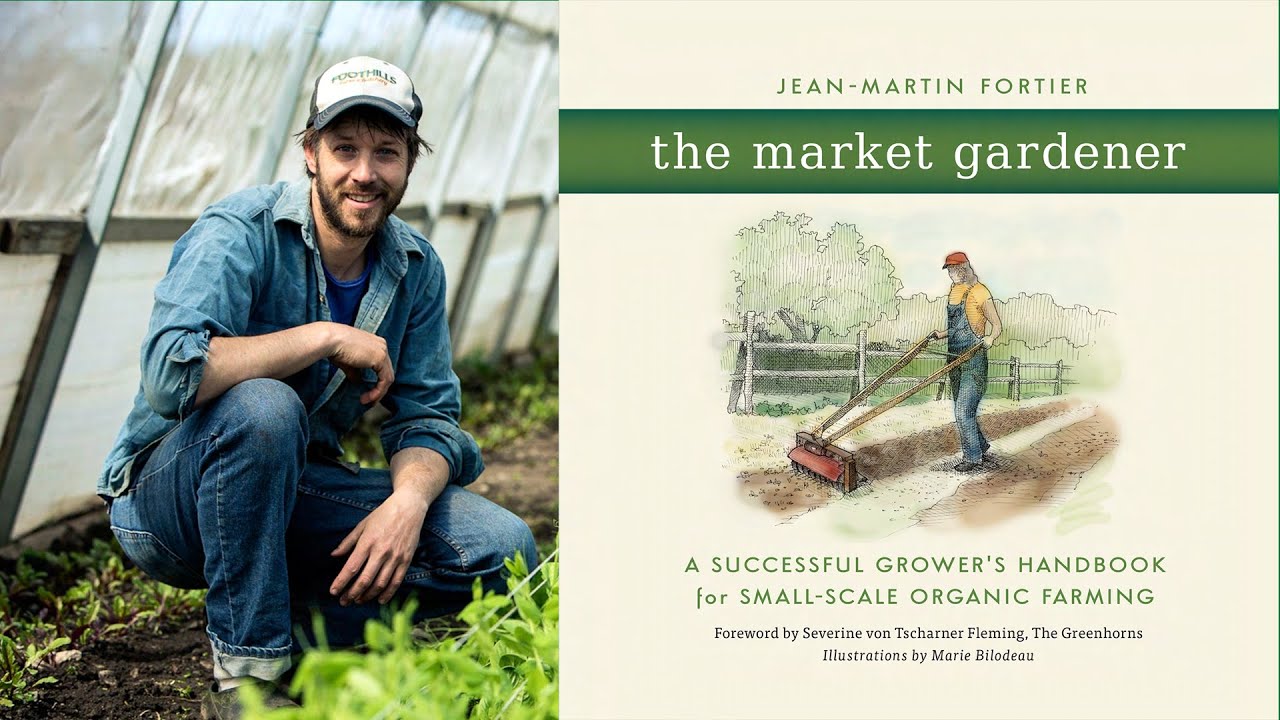

Les Jardins de la Grelinette farmer Jean-Martin Fortier, author of The Market Gardener moves Kristin’s CSA model to a small-scale organic farm right outside the city of St. Armand, Quebec, Canada. Like Kristin, Jean-Martin sells vegetables directly to consumers through CSA delivery. But he also grows and sells salad mix for local restaurants. Using only 1.5 acres of permanent raised beds, Jean-Marie grows 50 types of vegetables with help from only four full-time workers and two interns. His raised bed method requires no tractor. Soil is replenished with worms, toads, and compost, and crops are planted using a broad fork and deep rooting systems. Planting requires a hand-pushed seeder, and insects are controlled with nets. Because the soil is covered most of the time, there is little fungus, and crop planning allows larger harvests and more closely spaced vegetables. Covering shades out weeds and keeps in moisture. After showing his rock star farming methods, Jean-Martin highlights how his approach addresses both agribusiness and climate change problems. Replacing mass production with production by the masses will allow farmers to make a living, he explains. His approach aligns with United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moo’s arguments that biodiversity is needed to combat environmental consequences of climate change. A lack of bio-diversity may limit goods and services for the poor. Climate change has already negatively affected pollination by bats, birds, and bees and the richness of soils. Sustainable farming practices can help combat these problems.

The last segment highlights greenhouse manager Lauren Rathmell’s Lufa Farm in Montreal, Canada. In the farm’s urban greenhouses, Lauren and her crew grow a variety of hydroponic vegetables, including eggplant, peppers, cucumbers, and tomatoes, for basket subscription holders around the city. Here the CSA contents depend on customer orders, and boxes are delivered throughout Montreal. The sequence describes and illustrates the growing process in these rooftop greenhouses. Although not certified organic, the goal is a limited carbon footprint and an adherence to as many organic rules as possible. They combat insects with insects, for example, use butterflies to pollinate and reuse water through a fully closed loop system. They harvest rainwater to reduce water consumption, as well. But because vegetables are grown hydroponically, synthetic fertilizers must be used. With 5000 subscribers, Lufa Farm relies on fifty workers to produce enough vegetables to fill and deliver box orders. This last segment shows us an alternative perspective on urban farming that stresses mechanized sustainability with less emphasis on social and environmental development. It also links to a recent debate between traditional and hydroponic organic farming. According to Wilson Ring, some farmers argue the synthetic process hydroponic farming requires does not warrant an organic label. Hydroponic urban farming may also limit sustainability.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/55997615/shutterstock_384332770.0.jpg)